A Matrix of Creativity

(Originally printed in the L.A. Times Calendar

section, April 19, 1998)

Joseph Stern's Melrose company has been a local

innovator for five years. It moves ahead again as it stages its first new

plays.

By Jan Breslauer

With

20 years of acting and 20 years of producing both theater and television

to his credit, Joseph Stern has played a lot of parts. But to hear him

tell it, he seems at last to have found the role of his life—as the man

who made double casting a term of art.

With

20 years of acting and 20 years of producing both theater and television

to his credit, Joseph Stern has played a lot of parts. But to hear him

tell it, he seems at last to have found the role of his life—as the man

who made double casting a term of art.

A longtime force on the Los Angeles theater scene, Stern, 57, has been

putting on plays at the Matrix Theatre since 1980. Following a three-year

stint in New York producing the NBC-TV series "Law & Order," he relaunched

the Matrix company in 1993. But this time he had a new tactic.

Stern's twist was to cast two actors in each part, and to shuffle the

schedule so the ensemble could change with each performance. That way he

figured he'd be able to attract the kind of high-caliber performers who

normally wouldn't commit to a play for fear of having to pass up the TV or

film work that might come along. The system has worked, or so the awards

the company has been collecting would suggest. From the Los Angeles Drama

Critics Circle alone, the group has received; outstanding production 1993

("The Tavern"), '94 ("The Seagull") and '95 ("The Homecoming"), as well as

best ensemble for 19%'s "Mad Forest."

Currently, the Matrix company is preparing to open what may be its most

ambitious effort yet: a season of two new American plays in repertory. The

West Coast premiere of Wendy MacLeod, "The Water Children," directed by

Lisa James, opens on Saturday and next Sunday and the premiere run of

Larry Atlas' "Yield of the Long Bond," directed by Andrew J. Robinson,

opens on May 14 and 15. That the company is now able to tackle

putting on two new plays in repertory suggests just how successful Stern

has been. In fact, the company has thrived in ways even he didn't

anticipate.

"This double casting started five years ago as a stunt to facilitate

people to have jobs," says the amiable and outgoing Stern. "But what's

happened here is that in this five years this environment has encouraged

people to be better because they feel safe. Something happened that

eliminated all the competitiveness. It allowed people to get rid of their

agendas and just trust the situation.

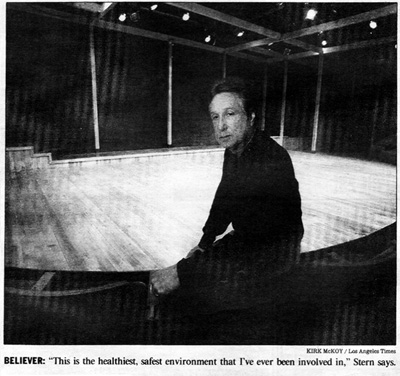

"I believe that this is the healthiest, safest environment that I've ever

been involved in, as a producer or actor, and that it is directly related

to this paradigm of [the] double cast," he continues. "I believe that with

my whole heart. I know it sounds like religious fervor, but I tell you,

it's been remarkable."

He is seated, with a large takeout cup of coffee in hand, in a rolling

desk chair on the polished wood floor of the empty set where "The Water

Children" and "Yield of the Long Bond" will play.

|

"This double casting started five years ago as a stunt

to facilitate people to have jobs. But what's happened here is that in

this five years this environment has encouraged people to be better

because they feel safe... I believe that this is the healthiest, safest

environment that I've ever been involved in, as a producer or actor..."

- Joseph Stern |

Stern had wanted to do new plays when he first relaunched the Matrix, but

was persuaded against it by the difficulty they can pose at the box

office. "New plays are very risky, and you don't always know if they're

going to work," he says. "There's a finite amount of money to run this

theater: There are no grants, no dues, nothing. The plays have to succeed,

to a certain extent."

He was also concerned about the suitability of the Matrix process to a new

work. "With this process, I began to feel that it was hard to do a new

play, because the writer and the director are denied the continuity of the

same actors day after day," says Stern. "Also, when you get to perform

here, they're one on, one off: You can't give a note that night and come

back the next night and do it. So you need very skillful actors to do

this."

Years of watching the development of the ensemble, which includes a core

group of more than a dozen Matrix regulars, however, have persuaded him

otherwise. And yet Stern knows he's chosen challenging material.

"The Water Children," which premiered at Playwrights Horizons in New York

last year, is about no less an incendiary topic than abortion. "It's about

one woman's experience, and then it moves to a spiritual place," says

Stern. "I never thought about the spiritual middle ground, which is what

this play deals with—that there are spiritual issues beyond' being for or

against abortion, and that it is possible to be pro-choice and still deal

with abortion as a spiritual experience."

Likewise, "Yield of the Long Bond," which is receiving its first staging

ever here, tackles issues that are both philosophical and personal. "To

oversimplify, it is about religion and money and how it stops us, perhaps,

from intimacy and what goes on in our relationships," says Stern. "It

deals with the strongest themes in our life."

But the Matrix actors and directors whom Stern consulted expressed

enthusiasm for the scripts, and that was good enough for him. That kind of

unpretentious attitude is, in fact, characteristic of Stern.

In his enthusiasm, Stern makes a visitor feel he has all the time in the

world—although this is plainly not the case. After all, he not only runs

the Matrix—where he's as likely to be performing a producer's normal

duties as dashing out to get the flyers printed, if that's what needs to

be done—but also maintains a full-time career as a television producer

developing new shows, under contract to Paramount. Yet for all his

obligations, Stern also comes across as a warm, unaffected and

good-humored man with a genuine interest in all matters theatrical—the

kind of guy who inspires loyal troupes, as indeed he does.

Actor David Dukes ("The Mommies" on TV; "Broken Glass" on Broadway), for

instance, has appeared in three previous Matrix shows and will be seen in

"Yield of the Long Bond." "This project started because it was the only

way we could all afford to work in the theater," Dukes says. "But this

process has become the most interesting thing.

"Being able to share the part requires constant conversation among

everybody. You go deeper and further than you might go on your own. I look

forward to the camaraderie and the challenge. Because you get to sit back

and watch your character done by someone else, you get a bit of a

director's eye as well. It's the best of all possible worlds."

Director Robinson, who has staged several plays at the Matrix, also sings

the praises of the double-cast process. "It is harder on the director than

anybody else," he admits. "But when you have two actors working on the

same role, the information that comes out is incredibly valuable.

"The actor has to let go of any proprietary claim on the material, [the

notion] that somehow the finger of God touched him or her to play this

role," continues Robinson, who is also an actor himself. "For some, it's a

real challenge, but the collegial atmosphere that takes over is a joy in

that we're all working together to solve the same problem."'

One reason for the collective bonhomie is Stern's particular approach to

double casting: He seldom puts two actors of similar type in a role. "We

cast very different people in each part," he explains. "The thesis was

that you can tell the truth in more than one way, which was self-evident,

but people don't think about that. "We did that purposely with almost all

the parts, as much as we could," he continues. "We began to use the same

actors over and over again, and everybody began to rehearse together. So

you can walk in here and an actor is rehearsing a scene and they stop and

the director talks to the partner out here [in the house] and they talk

back [to the actor onstage]. It's a three-way conversation. It's an

amazing process, really."

Most amazing of all, perhaps, is that it allows actors who thought they'd

never do theater in L.A. again to get back up on the boards. "I think they

come here and they've given up on their dreams," says Stern. "Most of the

company is middle-aged and older. They haven't done a play in years—

that's what I hear over and over. But they come in here and they find

process and love and nurturing. It's a real actors' theater. And I think

it brings out the best in them."

Jan Breslauer is a regular contributor to Calendar.