PERFORMANCE FOCUS: Not Nothing

Profile on the Matrix Theatre Company's 2000 production of

Waiting For Godot

(Originally printed in BackStage West, February 17,

2000)

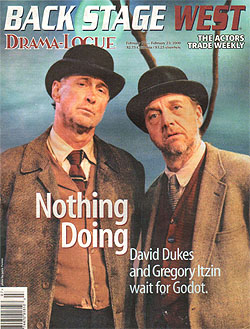

David Dukes and Gregory Itzin bring a unifying sense to the

moment-to-moment world of Beckett's "Waiting For Godot."

by Scott Proudfit

photos by Jamie Palmer & I.C. Rapoport

There's

an apocryphal story about playwright Harold Pinter which provides an

interesting lead-in to the examination of successfully taking on a role in

a Beckett play. After attending one of Pinter's cryptic productions,

The Caretaker, a woman wrote the playwright a letter which read,

"After seeing your show, I have only three questions: Who were these men?

What did they do for a living? And why should I care about them?"

Reportedly, Pinter wrote back, "I will answer your questions, but first,

please tell me: Who are you? What do you do for a living? And why should I

care about you?"

There's

an apocryphal story about playwright Harold Pinter which provides an

interesting lead-in to the examination of successfully taking on a role in

a Beckett play. After attending one of Pinter's cryptic productions,

The Caretaker, a woman wrote the playwright a letter which read,

"After seeing your show, I have only three questions: Who were these men?

What did they do for a living? And why should I care about them?"

Reportedly, Pinter wrote back, "I will answer your questions, but first,

please tell me: Who are you? What do you do for a living? And why should I

care about you?"

Pinter's point, of course, is that drama does not necessarily rest in a

character's backstory - the who, what, where, and why of his life. Rather,

drama rises out of relationships-the struggle of one person against

another onstage. And as Pinter would acknowledge, the father of the

avant-garde playwrights, Samuel Beckett, no doubt made this point well

before Pinter's plays hit the stage.

While this clever anecdote-true or not-provides some insight into modern

storytelling onstage, it is little help to an actor faced with the

challenge of performing one of these "undefined" Pinter or Beckett

characters. For, as all good American Method actors know, the who, what,

where, and why of any character, from Hamlet to Hannibal Lecter, are very

important when it comes to delivering the goods. David Dukes and Gregory

Itzin, double-cast as Vladimir in the new Matrix Theatre production of

Waiting for Godot, have faced just this quandary, and have shared

their experiences with Back Stage West in a pair of interviews,

midway through rehearsals and midway through previews.

The way these two actors came to terms with the unique situation that

playwrights like Beckett pose for performers provides invaluable examples

for those who one day wish to take on the avant-garde classics, as well as

those working on contemporary plays in which the information an actor

loves to cling to is not readily at hand.

Waiting for a Good Production

Widely acknowledged as one of the most important- if not the most

important-plays of the 20th century, Waiting for Godot has

nevertheless rarely enjoyed a successful run in the United States since

its critically divided New York debut in 1955 with legendary comedian Bert

Lahr as Estragon and E.G. Marshall as Vladimir.

The first of its kind, Godot is a play in which "nothing happens."

In Act One, two men, Vladimir and Estragon - transients? the two thieves

crucified with Christ? ghosts? - pass the time while awaiting instructions

from their master/benefactor. They encounter a ridiculous blowhard named

Pozzo and his elderly, and periodically verbose, slave, Lucky; they fight,

play verbal games, and comfort each other. Eventually, a boy shows up with

a message from Godot: He's not coming. In Act Two, the same thing

happens.

Obscure and ridiculous, the play has historically drawn as much ire as

praise from critics and audiences alike, partly because it has often

seemed more comfortable in the realm of academia than entertainment.

As Eric Bentley wrote regarding the Lahr production, "In general, the

Broadway critics are not intellectuals, and as to whether they are for

intellectuality or against it, are like the American people, divided about

50/50." It also has not helped productions that, despite its lack of

popular appeal, Godot was immediately accepted as a "significant

work" worthy of study in our universities. Indeed, more academic

criticism has been written about this play in the past 45 years than any

other. And interpretations have ranged from the Marxist to the Christian

to the purely linguistic.

|

"You can't give the message to the audience.

You can only give them the moment-to-moment dilemma. And if you do

it well, part of it will go across the boards."

- Gregory Itzin |

Considering its performance history and reputation,

Godot carries with it a lot of baggage, a fact that Dukes and Itzin

readily acknowledged.

"In the productions of Godot that I have seen — and I certainly

haven't seen them all — it's not a play," said Dukes. "It doesn't have the

energy of theatre. It has the energy of a soapbox piece or a literary

piece. And I think that finally kills most audiences; it drives them

away. When they talk to friends over dinner and coffee afterwards, they

don't have a warm response to it."

Both actors, however, felt that part of the play's infamous production

history is due to the fact that it is rarely done correctly. As Itzin

pointed out, "It's like with Shakespeare. There are people out there who

say, 'I don't like Shakespeare.' And I say, 'Well, you haven't seen it,

then. If you've seen it done right, you wouldn't give me that bullshit.'"

Yet Itzin and Dukes also acknowledged that all the blame for the spotty

production history cannot be attributed to lazy audiences and poor

execution. After all, Beckett set out to write an anti-theatre piece of

theatre, and that he did. Said Itzin, 'Why are there so few successful

productions? Perhaps it's built in. Endgame is an hour and a half,

and that's as long as it should be. But Godot is two and a half

hours long, and it's about waiting. It's that long because it is

about waiting. I'm sure Beckett did this going. 'Hee, hee, hee.' But

it's a built-in difficulty with this play."

It Takes Two

It Takes Two

Despite the daunting prospects, Dukes and Itzin in both interviews were

nevertheless confident in their director, Andrew J. Robinson. They were

further comforted by the fact that as with all Matrix productions, when

fears arise, there is always the support of a partner near at hand—the

person with whom you are sharing the role.

All Matrix Theatre shows are double cast for two reasons, as Itzin

explained, one economic and one artistic. "If you can allow actors to go

out and make money during the course of a run or a rehearsal process, then

you will get good actors," he said. "Otherwise, the problem with Equity

Waiver is you get paid no money and it's a huge time commitment and you

lose people right and left, because we're here in this town to pursue

careers and to make money."

Itzin and Dukes, though very different in look and attitude, are similar

in that both are Matrix mainstays and journeyman actors who have as many

credits in film and TV as they have on the stage. They emphasized time and

again that their approach to Vladimir is intrinsically tied to the other

benefit of double casting — the artistic dividends of working on a role

opposite a peer, something they have both come to appreciate over the

years.

Said Dukes, "I think that the dynamic that comes about in the act of

sharing a part changes your entire focus as an actor. Because one comes in

and one is a little ego-driven; your performance is wry important to you.

And when you're sharing, it still is, but it can't be the important

thing. You have to focus on the character. And when you are sharing, you

get to look at the character in action and that changes your whole vision.

With the act of doing and then having to talk about it with someone and

agreeing on choices, you really see what you have to do to make a scene

work. And it's clearer, at least for me, sitting out in the audience than

it is being in it sometimes, because you can't see the forest for the

trees."

Ever since the Matrix Theatre's successful production of Beckett's

Endgame in 1995, Robinson and the actors have been eager to take on

the playwright's masterwork. In late November, the cast first sat down for

a table reading, but things have only proceeded apace since a written-down

production schedule was drawn up in early January. Both casts attend

rehearsals together and watch each other's work; whoever arrives first

gets on his feet first for each role. Basic blocking is agreed upon. But

acting choices may ultimately be different for the two actors snaring the

part.

"Stealing is at a premium," Itzin said. "If David does something that

really knocks me out, I can use it. Because even if we could choose

to do exactly the same action and exactly the same objectives, it would

still be entirely different because he is who he is and I am who I am."

"And then there are moments when we disagree," added Dukes. "You did it

that way. all right — I'm going to do it this way, because

that doesn't work for me. But what becomes very clear is that the

character has to do something at that point."

Trust the Text

One of the difficulties with performing in Godot is that there is no

logical progression of actions, as one typically finds in more linear

plays. Vladimir and Estragon pass the time in many different ways, hut the

arc of their actions is not necessarily apparent.

Said Itzin, "Some of the criticism I read has said, and I believe it's

true, that every person onstage has what we now call Alzheimer's. They can

say something, aver something, say it was so, and then a sentence later,

not even be sure they said it. Does that lead to interesting acting

problems? Yes. it does." Dukes agreed: "Because the characters are

required to forget and the play is so repetitive with variations, it's a

devil to keep the development going."

The solution for both actors was to make the moment-to-moment work alive,

and trust that the arc will reveal itself. The result is a kind of

balancing act between clown work and tragic poetry — which of course, is

the balancing act that Beckett achieved in his best writing. Godot

has been intrinsically linked to the clown traditions of the music hall

and vaudeville since Lahr first performed it.

Mike Nichols' 1988 Broadway production, with Steve Martin, Robin Williams

and Bill Irwin. is a good example of the connection between clowning and

Beckett. Yet most critics agreed that this production, despite inspired

moments, was overall a disappointment. The antics of the clowns came at

the expense of the text. As Dukes, who saw the production, put it, "It was

pearls with no string to make it a necklace."

The difficulty for actors in Godot, as Dukes explained, is finding

the relationship between the moment-to-moment clowning and the overall

reverberation. As ltzin put it: "We're trying to find the meat, while

still serving the comic needs of the piece. There's a rhythm to it: there

are specific stage directions that are bits, essentially. To feel

satisfied in the reality of it at the same time as you're

performing—that's the hardest part."

"These two guys, especially Vladimir, are trying not to be foolish, but

constantly find themselves in vaudeville and music hall routines," said

Dukes. "They're stuck in this life and they cant get out of it. And its

horrifying. It's not just that they're clowns. It's, how are you silly

without ever intending to be silly? That echoes in every one of these

silly moments — the alternation between being very silly and very serious.

To find that will be a constant battle through the whole course of the

run."

The process for initially attacking Godot was simply making

choices in rehearsal, both actors explained, whether those choices

ultimately paid off or not. And ultimately both found that the text really

supported them in finding the balance they were seeking. "Beckett was also

a poet, and the starting point with all good literature is the words."

said Itzin. "The rhythm tells you something; the rhythm delivers something

to the audience and to you."

"And the fact that a silence comes here, a silence comes there, you have

to build," Dukes added. "If the silence is going to work, something has to

happen to cause the silence. You cant just have a stop. Those pauses, as

in Pinter, direct your attention."

Relying on the text is more difficult than it sounds, particularly for two

actors who work so much in other media.

"You want to embroider it." admitted Itzin. Because we all come from our

TV traditions where you fix things or you bring your spin to something.

And that's how you keep employed, taking dross and turning it into gold.

That's your first impulse here, too. When you can't figure something out,

work it or spinit or take a lot of time with it. Ultimately, I think we've

found that to do it the way it's written is the best way. Rut we had to do

the trial and error to gel back to that point."

A Question of

Character

A Question of

Character

Once the primary challenge of Godot — combining the clowning with

the darkness — has been faced, the question still remains, Who is

Vladimir? Both Dukes and Itzin felt this question could be answered for

the actor playing him, but not in the traditional sense.

"In Godot, backstory and inner monologue are not important,"

explained Dukes. "Beckett didn't write that and he didn't care about it.

What's important is what they're doing and how they're trying to get

through the day. You can invent what you need, but he didn't need it,

because he didn't feel that background was necessary to the story."

Rather, as in Pinter, relationship between the characters in Beckett's

plays is of central importance. Therefore, ltzin and Dukes carefully mined

the text examining the central relationship between Vladimir and Estragon

(who's played by John Vickery or Robin Gammell, depending on the evening).

"We discovered in rehearsal that it's like a marriage." said Dukes. "When

one is one way. the other has to be the opposite. It alternates to a

certain extent."

Because so much that goes on between these two clowns in the play boils

down to nonsense, in reading the play they sometimes seem like the same

voice split between two characters. But closer examination of clues in the

text reveals that Vladimir and Estragon are very different and that their

relationship is something very similar to that which Itzin and Dukes

describe.

"If you notice, Vladimir doesn't eat," observed Itzin. "So as a Method

actor, what do you do with that? I don't know. Do you think about him

being hungry? Does that help you? I early on had the hit that Vladimir was

the wife in the relationship. It doesn't necessarily hold water all the

way through, but Estragon is always trying to sleep; 'Leave me alone, and

feed me and take care of me.' I think that men are basically the babies,

and women, like Vladimir, say, 'What about me? Nobody suffers but you?'

There it is. Vladimir says it. Actually, I could see it even more

delineated than David and I are playing it, more along those gender

lines." The simple fact that Vladimir doesn't eat can lead to other

discoveries for the actor, as Dukes explained. "One of the reasons that he

can't eat is that his mind is always racing. I know that's what it should

be. I've clued into that in my thinking, but not necessarily in my acting

yet. It's why he always walks agitatedly. Estragon is always sitting down

and Vladimir is always in motion. I think it's because he has a mind that

won't stop and he's trying to come up with answers. It's an average

mind that wants the big answers and can't get them. And even if he does,

he's still going to die. I think Vladimir is just churning."

It would seem that making sense of these clues and clearly playing the

relationships is a recipe for success when taking on the great roles in

Beckett. But is Vladimir really a great role? (This is not such a silly

question considering the fact that "Performance Focus" is, in some way, a

profile of great actors in great roles.) Said Dukes, "I'm not sure it's a

great role. I don't know if you can divide him from Estragon. I think the

two of them are great parts. but they have to be together. It's the fact

that it's a marriage. They may be two male friends, but it's a marriage.

They are two people getting through. So in that sense, it's not a great

part on its own. It's not Hamlet or Lear. But if you can get all the

comedy of the play, as well as living in the nothingness with no hope — if

you can do that, it's a great part."

Just Do the Lines

It's interesting that both actors came to the conclusion that the text of

Godot by itself has all the information needed to give a great

performance, particularly in light of Beckett's famous insistence to

actors. "Just do my lines. Don't act."

Yet, as much as both performers recommended trusting the text, Dukes and

Itzin warned of the dangers of laying hack and believing the text will do

all of the work.

"That's the reason so many people walk out of this thing." said Dukes.

"Because performers think. There are so many choices. I'll just do it flat

and let the audience come up with the meaning. I don't, as an audience

member, expect a performer to do all of the work, but they have to do some

of the work.

"Waiting for Godot is great, but you can't approach it like it is

great," Dukes continued. "1 think that finally it can still be

anti-theatre without the flat, boring readings. If we can keep the

audience from coughing for an hour at a time, and then at the end they

realize nothing happened, that's anti-theatre. Nothing happened, but it

was absolutely filled, just like it was for Vladimir and Estragon."

I was able to catch two preview performances of Godot prior to the

second interview, and in this writer's opinion Dukes and Itzin, with

credit to director Robinson, achieved the goals they set out for

themselves. Not only did both actors seem to strike an electrifying

balance between the comic and the tragic, but the acts of the play moved

along at a clip from humorous moment to humorous moment. And only at the

intermission and again walking home did I take pause and remember that

nothing had happened — "nothing" only in terms of plot, of course, because

so much happens in Waiting for Godot, and, as ltzin and Dukes

demonstrated, not only for the audience.

For the first time in production, for this writer at least, it was

apparent the transformation that Vladimir goes through in the play, from

antic questioner to resigned philosopher. The arc behind the clowning was

revealed, and the effect was profound.

Telling Struggles

Telling Struggles

During rehearsals. Dukes and Itzin each related something of particular

concern to them at that point in their process. By the second interview,

after a week of previews, they had begun to deal with these problem areas

— and how they did so revealed much about the ongoing work required by the

great plays, and of the intelligence and humor of these two actors.

Dukes was having trouble bringing reality to a section of the play in Act

Two when Pozzo, Lucky, Estragon and Vladimir have all fallen down and

can't get up. It's presented as a vaudeville routine: One tries to help

the other who's fallen and falls himself. Despite Dukes' concerns, seeing

it in performance, the section works. It's funny, and at the same time an

interesting though brief interlude from Vladimir's constant probing — and

a moment for Estragon to enjoy a passing cloud.

Dukes, midway through previews, said, "It's still a troublesome section. I

don't know that I have found a human thing for it yet. It's just bizarre.

Vladimir gets there and he can't get up. And it terrifies him for a while.

He tries to accept it, but he never quite settles into it. He sort

of catches his breath for a minute. I have to just make it very personal

and let it fall where it may."

Perhaps it is precisely Dukes' concentration on trying to come to grips

with this piece of business in performance that makes him particularly

shine in this section. As he and Itzin have both sought to do throughout,

his panic seems to give a grounding to the vaudeville bit, and a tense

balance is struck between the clowning and the pathetically human.

For ltzin, the concern in rehearsals was just conveying the message of the

play while keeping the bits working at full steam. He related this

specific experience, midway through previews: "There's a scene near the

end where Vladimir says, 'We have kept our appointment. How many people

can say as much?' And Estragon says. 'Billions.' And the point is,

Estragon's right. That's what everybody does on this planet. We're

all getting through the best way we know how. That hit me opening night.

"So then I tried to deliver that speech the next time, keeping in mind

that universality, and it meant nothing. It was dead. Because what's

important is that it's peculiar to their dilemma. If the audience wants to

get it, fine, but you can't say it to them. You can't give the message to

the audience. You can only give them the moment-to-moment dilemma. And if

you do it well, part of it will go across the boards."

Like the balance Dukes was still working on in the falling-down bit,

Itzin's struggle with this section of the play seems to get to the heart

of performing Beckett. As both actors would agree, Beckett, like all great

writers, does much of the work for you. But if you lay back and rest in

the text the audience will check out — and on the other hand if, as Itzin

did. you push the message too obviously, you'll kill it.

It goes to show that performing the great roles in Beckett is as much of a

balancing act as are the vaudeville bits that the playwright copiously

depicted in Waiting for Godot. As David Dukes and Gregory Itzin

both demonstrate in performance, they are two actors with the strength,

dexterity, and perseverance to pull off this desperate balance with

apparent ease.