REVIEW: VARIETY, Wednesday, October 15, 1969

Josh Productions (William Devane and Joseph Stern), in association with

Moe Weise, presentation of drama in three parts by Thomas Murphy. Staged

by Arvin Brown; setting, Kert Lundell; lighting, Ron Wallace; costumes,

Vanessa James; production Stage manager, James O'Connell; general manager,

Gugieotli & Black; company manager, J. Ross Stewart; publicity, Max Eisen;

associates, Warren Pincus, Cheryl Sue Dolby. Opened Oct. 8, '69, at the

Mercury Theatre, N.Y.; $6.50 top Tues.-Thurs., $6.95 Fri.-Sun.

Harry Carney........... Charles Cioffi

Hugo Carney........... Anthony Palmer

Betty Carney ......... Roberta Maxwell

Mush O'Reilly...... Dermot McNamara

Iggy Carney............... Don Plumley

Michael Carney............Michael McGuire

Michael Carney Sr. ....; Stephen Elliott

Des Carney ................ Tom Atkins

First produced in London eight years ago, and preemed in the U.S, two

seasons ago at New Haven's Long Wharf Theatre, "A. Whistle in the

Dark" has finally made it to New York. It turns out to be well worth

the wait.

Thomas Murphy's drama is legit-in-the-raw, a consistently absorbing,

blisteringly powerful theatre piece that leaves a spectator exhausted but

exhilarated. Despite a profoundly unpleasant theme and savage characters,

the play and the production are of such high quality that it's a prospect

for a fair run. If this play can't draw off - Broadway audiences, serious

drama in New York is in trouble.

The corrosive effects of living by a mindless code of virility are

persuasively set forth in ''Whistle." More than just a fashionable tract

against violence, the play is a rich and psychologically plausible study

of a fascinatingly differentiated family, as well 93 «t» eloquent

sociological document about lower-middleclass life.

The characters are Irish immigrants in England. The oldest of five

brothers, who has a lowpaying but respectable job in Coventry and is

comfortably married to a British girl, is visited by his clan.

First, the three most brutal of his brothers who quickly take control 61

the household. Then comes his youngest, least savage sibling and his

blowhard father. The conflict arises from the attempts of the elder

brother to wean the youngest from this nest of vipers. Both are destroyed

in the process.

In view of the current violent conflict in Northern Ireland, the play

has special pertinence, although it was written a decade ago. It's quite

old fashioned in construction, with a distinct beginning, middle and end,

but it's not pat and it consistently grips interest. Credibility is

occasionally strained for dramatic effect, particularly in the conclusion,

but the play has an inexorable sweep that transcends details.

The family in this play is as hair-raising a brood as any in Jacobean

drama. In their relish of blood sport and inability to come to terms with

society on any level but the physically destructive, they suggest a mob

of superannuated medieval mercenaries. But the author has made them live

on the stage.

The older brother, torn between a sense of decency, physical fear and

atavistic roots, is a compellingly complex character. The father is a

fraud and a failure,. who has warped his children's psyches to

compensate for his own inadequacy, but he has the redeeming gift of charm,

and becomes a memorable stage creation. The most vicious of the brothers

is a study in pure malevolence. He is not without intelligence, and his

raging third-act justification of his view of life is superbly written.

Several of the players in this production originated their roles two

years ago at the Long Wharf Theatre, and virtually the entire cast has a

predominantly regional legit background. The director, Arvin Brown. Is the

artistic director at Long Wharf. It adds up to a gold star for U.S.

regional theatre, for this production is brilliantly acted and superbly

staged.

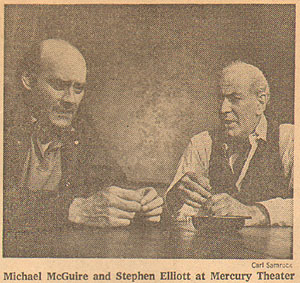

No performance falls below the level of superior, and there's a rare

sense of ensemble technique. Stephen Elliott turns in a virtuoso

portrayal as the phony patriarch, replete with fascinating detail but

never overdone.

Michael McGuire has perhaps the most difficult role as the indecisive eider brother, and he gives a subtle, intelligent, nuance-filled

characterization. Charles Cioffi, playing the most brutal of the clan, is literally horrifying.

He's an actor with an unusually powerful

presence and physical skill and his performance fastens itself to the

memory like a leech. Roberta Maxwell is lovely and touching as the

terrified, desperate wife, and Tom Atkins. Don Plumley, Anthony Palmer and

Dermot McNamara offer polished supporting portrayals.

Brown's staging is admirably disciplined and attentive to the play's

resonance, but the pitch is keyed at too high a level throughout. The

third act in particular is too emotionally draining, so by the time the

climax arrives an audience's capacity for reaction is depleted.

Kert Lundell has designed a playable and subtle setting of a

lower-middle-class parlor, and Ron Wallace's lighting is flavorful.

"Whistle" is the first producing venture of William Devane and Joseph

Stern, two-young actors, and it's an impressive managerial debut. The

film rights to the play were sold years ago, but the play might repay a

number of small "off - Broadway" editions in selected cities.

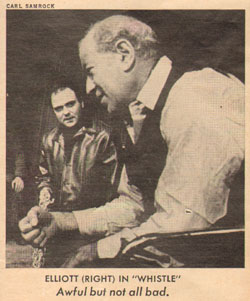

REVIEW: TIME MAGAZINE, Friday, October 17, 1969

Fall

of the House of Carney

Fall

of the House of Carney

The death knell of the realistic play is sounded

every season, and each season some play refutes it. A Whistle in

Me Dark is just such a drama. It has the raw, roiling

energy of life. It is full of the rude poetry of the commonplace. It

states truths about human nature that one would rather forget, and

reminds one that being born human is the alltime crisis of every man.

One of the pressure points of that crisis is the

family. The Carneys are a pride of Irish gutter lions. The father is a

drunkard, a bully and a braggart. When his boys were small children,

he routed them out of bed at 2 or 3 a.m. and set them to clouting each

other till they collapsed. Bred to the tooth and the claw, three of

the sons live as pimps, louts and barflies. A fourth son, Michael,

flees this world of lacerating animal instinct. He settles in

Coventry, marries an English girl and opts for a life of decency,

order and reason. But the clan Carney moves in with him like

blood-sucking Furies.

Paralyzed by Inadequacy. This is where

the play actually begins, and the events that follow have resonances

of The Homecoming — though Irish Playwright Thomas Murphy's

play was produced four years before Pinter's. The brothers make passes

at Michael's wife and even suggest using his home as a whorehouse.

Michael is faced down, raged at and humiliated by his father, who is a

perfect blend of aging bull and undiminished blarney. Michael's wife

urges him to stand up for his rights. But he is paralyzed by a nagging

sense of masculine inadequacy.

As the evening builds to a tragic climax, a

melancholy sense of the dooming, repetitive quality of family life

patterns grows with it. The playgoer is invaded and disturbed by a

sense of the lost ifs that determine people's lives. If the father had

not been an alcoholic, if some rays of civilized light had filtered

into the Carney home, if brute passions could be confined to the

brutes, if, if, if—a lament for humanity's near misses at achieving

humanity. For awful as they are, the Carneys are not all bad. They

have courage; they are loyal, they tell the truth, insofar as they can

see it. Their destiny is not to be evil but to be unable to mobilize

and release the good qualities that they have in them. It is the

playwright's essential fairness and depth of understanding of this

plight that give A Whistle in the Dark its strength, wisdom and

broody disconcerting beauty.

The performances are all labors of skill and love.

For a flawless delineation of the charm, bluster and pathos of the

self-conned father, Stephen Elliott's work should be studied by any

actor who ever cherished his craft. There is a silent music in Arvin

Brown's direction as he moves his players through arpeggios of

violence and a discriminating counterpoint of darkness and light to

give a final touch of distinction to a play worthy of every tribute.

REVIEW: "A Study of a Most Unpleasant Family"

New York Times, Thursday, October 9, 1969

"A Whistle in the Dark" Opens at the Mercury

Stephen Elliott Excels in Role of Father

By CLIVE BARNES

Thomas

Murphy's play, "A Whistle in the Dark," which opened at the Mercury

Theater last night, is a strange, ugly, impressive play. It was produced

originally in London, and a couple of seasons ago Arvin Brown staged its

American premiere for his Long Wharf Theater Company in New Haven. I saw,

and admired, the play there, and it was fundamentally the same production

— still with Mr. Brown directing and many of the original New Haven cast—

that has now been brought to New York.

Thomas

Murphy's play, "A Whistle in the Dark," which opened at the Mercury

Theater last night, is a strange, ugly, impressive play. It was produced

originally in London, and a couple of seasons ago Arvin Brown staged its

American premiere for his Long Wharf Theater Company in New Haven. I saw,

and admired, the play there, and it was fundamentally the same production

— still with Mr. Brown directing and many of the original New Haven cast—

that has now been brought to New York.

Seeing it at its final preview, I was once more struck

by the unusual vigor and directness of a play that interweaves themes of

violence, loyalty and cowardice in a study of one of the most unpleasant

families in stage history. My colleague, George Oppenheimer, has recently

written most attractively about stage characters he would not care to

invite home to dinner. Mr. Murphy's family here—"The Fighting Carneys" -

are hardly the kind of people you even invite home for a coffee. They are

thugs.

Yet there is a great deal more to Mr. Murphy's story

than a loving, at times rather melodramatic description of the face of

violence. There is in this play something of the horror, complexity and

final catharsis of a Greek tragedy. Mr. Murphy is not quite taut enough in

the construction of his play. He occasionally skids perilously close to

the belly laughs of 'bathos, and, if anything, he tends to overwrite. But

he has the stuff of drama in him and "A Whistle in the Dark" is a good,

rousing and gripping play.

It is the story of an Irish family—the Carneys. The

father is a fake, a bully and a drunk. A coward himself, he's brought up

his five sons to be street fighters, louts and bullies. When he had the

money he would come home drunk at 2 o'clock in the morning, wake up the

kids and force them to fight one another. Yet they loved him. He had the

lilting gift of the Irish.

At last one brother escapes from County Mayo, crosses

the Irish Channel, settles in the English town of Coventry and marries an

English girl. This is Michael, the odd-man-out in the family, who wants to

be respectable, to live in peace and to bring up his own children. The

play is the outlining of his tragedy.

First, three of his brothers leave Ireland to live with

him. Boisterous and layabouts, they destroy the carefully knit fabric of

his new life. Michael can make no contact with them. One night, coming

home, he is attacked by a Coventry gang. He cries for help, and almost

immediately his three brothers are there. A coward, Michael runs away. His

brothers will never forgive him. He will never forgive himself.

Eventually the father arrives, with the youngest of the

Carney brothers, a boy that Michael always hoped he would be able to

protect from the brutalizing atmosphere of his home environment.

Now Mr. Murphy, having set up the situation, puts

Michael, the blowhard father and the sickly tough brothers to their test

The brothers are challenged to a fight The violence escalates with a

pointlessness all the more horrible for being inevitable, and Michael is

cornered by his fate.

It is the kind of play that requires very careful

staging and acting. Its rambustoiusness is frankly old fashioned— compare

the stagey violence here, for example, with the stealthy convincing

violence of the movie "Easy Rider" and the point is instantly made. But

Mr. Murphy's dramatics can carry conviction, if they are given conviction,

and they are.

It is the success of Aryin Brown's staging that he

maintains the pressure without ever letting it boil over. Helped by

the seedy settings devised by Kert Lundell, Mr. Brown conrives to give the

play its full measure as a domestic tragedy, with all its miseries,

mistakes and pettiness.

The acting is first-rate. Stephen Elliott as the

father—singing songs of the old country, exercising his spurious

authority, and living vicariously off the violence of his sons—is

remarkable in that he wins our sympathy as well as demanding our loathing.

The shallow fakery of the man is evident, yet so also is that oddly deep

superficial charm.

The other outstanding performance is Charles Cioffi as

Harry, an ox of a man, swinging a bicycle chain, a pimp, a bully yet also

with a kind of heroic honesty in a diametric contrast to his father. Of

the others I might mention Roberta Maxwell's defiantly tattered little

wife, Michael McGuire's worried and disturbed Michael, and Don Plumley's

pathological yet occasionally honorable bully boy, Iggy. It all makes for

a disturbing yet far from unrewarding evening.