A 'Homecoming' Fit for Pinter

• Theater review: Director Andrew J. Robinson proves himself a rugged

interpreter of enigmatic drama in this fluid staging of the playwright's

1965 play.

by Laurie Winer

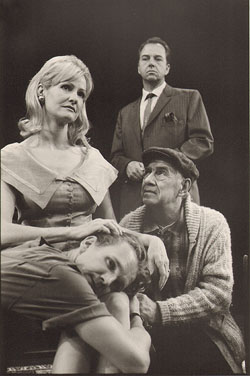

Clockwise from bottom L: Sebastian Roche,

Lynnda Ferguson, Gregory Itzin & Philip Baker Hall

The central event in Harold Pinter's 1965 play "The

Homecoming" is an ominous thing-puzzling, disturbing, sexually taut and

really weird. Critics have argued for years over the meaning of the

welcome received by a British professor when he brings his wife home from

America to meet the most sinister family this side of the Krays. Director

Andrew J. Robinson goes straight to the crooked heart of the play in this

new production at the Matrix Theatre in West Hollywood. His "Homecoming"

is as fluid and funny as a harrowing ride can be. The homestead into which

the professor brings his wife is a masculine domain, overseen by an aging

tyrant of a father, his emasculated brother and two sons, Lenny and Joey,

each one menacing in his own way. The men veer between respect for Ruth,

the professor's wife, and gross insult, with an emphasis on the latter.

Yet Ruth remains strangely unsullied, even when she is pawed.

As he did with his production of Samuel Beckett's

"Endgame" a few months ago at the Matrix, Robinson—who in another lifetime

played the hippie psychopath in "Dirty Harry"—proves himself a rugged

interpreter of enigmatic drama. His actors find comedy in depraved corners

of humanity, and they deliver finely etched performances in roles that

could be played as blandly archetypal.

Robinson has some kind of special bond, it would seem,

with the wonderful Gregory Itzin, who played the cowering Clov in

"Endgame." Here, as Lenny, Itzin radiates hostile potential while sitting

in an armchair picking horses to bet on from the newspaper. He is a

fastidious dresser; his narrow tie and dress socks all seem to indicate a

precision cruelty. When, through force of habit, his father threatens him,

Lenny answers with a calm, "Don't use your stick on me, Daddy. No,

please." His light sarcasm calls up some long-ago day when the boy

couldn't defend himself against the man, at the same time serving as a

chilling reminder that Lenny now has the means as well as the cause to

beat his old dad.

The smartest one in the family, Lenny is sarcastically

sure that no one in the room will be able to give him an answer when he

ventures a question such as "What do you make of all this business of

being and not being?" His working-class accent and bored expression are

very funny when he challenges Teddy, his ineffectual professor brother, to

a little verbal debate: "I want to ask you something. Do you detect a

certain logical incoherence in the central affirmations of Christian

theism?"

Granville Van Dusen's Teddy meets his brother's hostile

challenge with nothing but a supercilious stare; this is a man who seems

to believe he is holding onto his male dignity even as his family stomps

on it and then grinds its heel into it. As the other emasculated figure,

Uncle Sam, the self-styled "chauffeur" who drives people to the airport,

Howard Honig enters looking like an overworked undertaker. His tired face

collapses further and further under each fresh insult doled out by his

brother Max, the patriarch.

As Max, W. Morgan Sheppard looks like the latter-day

Hemingway, with a booming voice that creeps very low to a threat. In his

suspenders and cane, he is both frightening and pathetic as the aging,

once-terrifying character. It is the genius of the play, seen particularly

in Sheppard's performance, that it is both archetypal and very specific,

both metaphoric and realistic, at the same time.

Christian Svenson is appropriately Neanderthal and

squashed-looking as the amateur boxer Joey, whose lascivious looks at Ruth

help build the play's tension. As Ruth, ostensibly the victim of the men's

hostility, Sharon Lawrence shows she is in absolute control of the

situation at all times with her beauty-school posture and above-it-all

stare (she has the alluring, thick-lashed eyes of the original Barbie

doll). Her line readings, though, are a bit affected.

Set and lighting designer Neil Peter Jampolis has done

a superb job creating a living room that bespeaks long-ago better times

for the family. The feminine touch of the dead matriarch—seen in the

carefully chosen antimacassars on the faded sofa—has been all but

obliterated by male neglect. The entire room has a not-quite-clean gray

sheen, and there are water stains on the highest parts of the walls. Yet

clearly the room is also a shrine to the dead mother. It seems to hold the

secret to the play—it knows what went on there when the boys were young

and the mother was still there to protect them or not.

The Matrix offers two casts in "The Homecoming." The

actors playing mix and match with the ones I saw are Allan Arbus (Sam),

Lynnda Ferguson (Ruth), David Dukes (Teddy), Philip Baker Hall (Max),

Sebastian Roche (Joey) and Cotter Smith (Lenny).

Los Angeles Reader, December 8, 1995

Acting for Acting's Sake

• Matrix's Homecoming is an Exquisite Minuet of Menace

by Michael Frym

The Matrix Theatre Company's production of The

Homecoming is the finest rendition of Harold Pinter to hit L.A. stages

in years. Joseph Stern's group has once again proven it is the city's

surest ticket to quintessential, professional theater.

Pinter is unquestionably an actor's playwright — just

peruse a bit of the script, and you'll feel the drive to read it aloud. To

a greater extent than his other works, the success of The Homecoming

relies entirely on superb acting. Almost nothing else happens — just

acting. The playwright scores his script's nuances and pauses with the

precision and planning of a composer. Nothing is left to chance, and,

here, every taut, riveting beat is realized with menacing subtext by the

top-drawer cast. (As usual, the company double-casts each role, and mixes

the actors throughout the run of the show.)

Stagewise from his years as an actor, Pinter also knows

that words are not enough, that his dialogue needs a context to make the

intimidating impact of his dark script fully palpable. So, he provides

twisted, acutely dramatic conflicts, where animosity and terror result in

steamy undercurrents between his characters, which constantly threaten to

blow the lid off their glacial exteriors.

Pinter's point of view is coolly objective. The

Homecoming was his most lucrative commercial success, due largely to

its scandalous nature. Without moral judgment, it tells the story of a

crude father and former butcher, Max. (W. Morgan Sheppard), and his two

sensual sons, a wannabe boxer, Joey (Sebastian Roche), and a dangerous,

tightly wrapped pimp, Lenny (Gregory Itzin). Upon the surprise homecoming

of a third son, the unassertive college professor Teddy (David Dukes),

this Gorey-esque trio make a family "whore" of Teddy's wife, Ruth (Lynnda

Ferguson), with her laconic consent. All the characters accept this amoral

situation without comment or external feeling.

The Homecoming is values-free as well as plot-free.

The characters' actions have little relation to how most people would

behave in a similar situation, and more to do with what makes a

theatrically effective "moment." This disconnection results in an

omnipresent menace, which is totally out of proportion with the

circumstances that caused it, so each inference and curse masks a

potential snicker of farce. One could almost believe the whole endeavor is

Pinter's personal cosmic joke.

Andrew J. Robinson's economical direction trims any

acting excesses, leaving a lean, powerfully piercing work. At no point

does he lose control — every moment involves a specific choice, made in

concert by Robinson and his ensemble. The actors realize they are playing

"moments" and "Pinter pauses," and protect themselves: The cast

occasionally camps ever so slightly. Sheppard exudes a bizarre magnetism,

something akin to a crass, blarney-blabbering Irishman. He repeatedly

engages the audience as he spews his contempt indiscriminately at his sons

and his brother, Sam (Allan Arbus).

Dukes paints an intriguing Teddy, maintaining a feint

smile straight through events that are so humiliating, the audience

repeatedly wonders whether he'll crack under the strain. But, just as

Teddy is perceived as a doormat who is about to lose Ruth to his depraved

relatives, Dukes plants the suggestion that Teddy's return to the family

front is a premeditated decision to rid himself of a wife who's beneath

his station, while repaying his father and brothers for his upbringing. In

the end, he leaves — not the abandoned husband, but a victor realizing

closure on a bad chapter in his life.

Roche establishes Joey as a shell-shocked buffoon,

exquisitely bumbling and bestial in his amorous engagements with Ruth,

while Itzin plays Lenny as a man on the edge, who covers his violent

nature with feigned indifference. As Max's chauffeur brother, Arbus makes

use of the intrinsic awkwardness of this underdeveloped character. His

discomfort plays as an effort at normalcy in a consummately abnormal

situation. Ferguson is stunning with her icy calm — it's meticulous work,

as is all the company's craftsmanship.

The somber North London living room set, bathed in

stark lighting, is an artistic triumph for designer Neil Peter Jampolis.

In the end, The Homecoming surfaces as a play

constructed of the psychological substance that leads to paranoia and

repulsion — epitomized by the cast's expertly choreographed minuet of

menace.

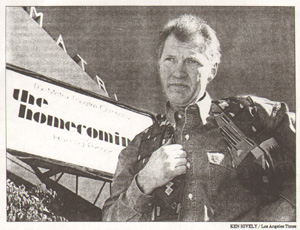

Feature Article: Los Angeles Times

He Knows How to Handle Evil

• Andrew J. Robinson has gone from 'Dirty Harry' villain to directing a

revival of Pinter's mean-spirited 'The Homecoming.'

by Janice Arkatov

As an actor,

Andrew J. Robinson knows a lot about evil. He bore into it headfirst as

the psycho-scumbag in the original "Dirty Harry," and later as killer Jack

Abbott in the Mark Taper Forum production of "In the Belly of the Beast."

He's back again now in those emotionally murky waters, directing a

critically acclaimed revival of "The Homecoming" (at the Matrix Theatre),

Harold Pinter's scabrous tale of a middle-aged man who brings his British

wife back from America into his family's London homestead.

As an actor,

Andrew J. Robinson knows a lot about evil. He bore into it headfirst as

the psycho-scumbag in the original "Dirty Harry," and later as killer Jack

Abbott in the Mark Taper Forum production of "In the Belly of the Beast."

He's back again now in those emotionally murky waters, directing a

critically acclaimed revival of "The Homecoming" (at the Matrix Theatre),

Harold Pinter's scabrous tale of a middle-aged man who brings his British

wife back from America into his family's London homestead.

"It's a tough, mean play," acknowledges

Robinson, 53, a founding member of the in-house Matrix Theatre Company.

"And that's what's so difficult about doing it. You have to go to that

dark side in yourself, remember the choices you made in your life that

you're not proud of—but you have to cop to. I think the success of this

production is based on the consensus we've achieved as a company: coming

up with the stories below the surface, bringing to the playing experience

our human experience."

Complicating matters, perhaps, is the

fact that Robinson (whose TV credits include the recurring role of Garak

in "Star Trek: Deep Space Nine" and the title role in the ABC movie

"Liberace") has double-cast the piece—meaning he has 12 actors creating 12

different characterizations for six roles.

"I'm a big proponent of double-casting,"

stresses the actor, who was doubled in Matrix productions of "Habeas

Corpus" and "The Tavern" and directed a well-received double-cast revival

of Samuel Beckett's "Endgame" last summer. (A reprise staging of "Endgame"

will open March 14.) Beyond practical concerns—the

company is made up of professional actors who need the flexibility to

pursue TV and film work—Robinson enjoys the aesthetic of the expanded

creative process.

"Everyone comes to every rehearsal," he

says proudly. "Sometimes it's like a tag team. In the middle of a scene,

the actors switch: 'Now you go up there.' Or we do shadowing; one actor is

onstage, the other is there almost as a doppelganger."

Robinson acknowledges it's not always an

easy fit. "A lot of the actors had some resistance at first: 'It's my

role, my choices, my answers!' But as people give up that propriety, they

begin working on the role together, leveraging the play for information:

how to play a moment, find a subtext, even a simple blocking."

Potentially daunting for Robinson was

that, before "Endgame," he had not directed professionally for 15 years.

But returning, he says, was like getting back on the proverbial bicycle.

"Except," he says cheerfully, "that

working with people of this caliber, it was a streamlined, top-of-the-line

bicycle. I like to work as a director as I do an actor—as a collaborator.

So one of the tools I picked up was [saying] 'I don't know.' I

found such power, such trust that I wasn't going to pretend [or]

answer something when I didn't know."

Still, he admits being intimidated— and regularly

challenged. "These people are doing this for no money, for the love of the

craft. They're not going to fart around."

The New York-born Robinson was 3 when his father was

killed in World War II. (Since directing "Endgame," he's been using his

middle initial "J." as a tribute to his maternal grandfather Jordt, whom,

he says, "was the main male influence in my early life.")

"It was basically a terrible childhood," the actor

says, gently referring to his late, much-married mother who battled

alcoholism and a nervous breakdown. At 10, he made his acting debut as a

shepherd in a school Christmas play. "I was pretty pumped; people were

watching me."

Later, he attended the London Academy of Music and

Dramatic Art as a Fulbright scholar, and after graduation spent the next

few years in repertory in Milwaukee, Cincinnati, Providence, R.I., and

Philadelphia.

In 1971, Robinson was tapped for the bad-guy role in

"Dirty Harry." (He was the sniveling recipient of Clint Eastwood's famous,

climactic gun-wielding taunt: "You could ask yourself a question, 'Do I

feel lucky?' Well, do ya, punk?") "With that film, I gained my career and

lost my career," the actor says with a sigh. "I felt very proud of my

work, but it ended up being such a scurrilous, despicable character that

people didn't want to know from me. It was a hard pill to swallow."

Robinson retreated to New York (where he and director Joel Zwick had run a

theater company in the late '60s) and didn't return to L.A. until 1978,

when TV roles started coming in. Yet he quickly grew disenchanted with the

quality of work being offered him, and in 1980, after a particularly

"horrendous" experience on TV's "The A-Team," he essentially quit the

business, selling his L.A. home and moving to Idyllwild, Calif.

There, he and his wife, Irene, (they'll be married 26

years in March, and between them have three children and two

grandchildren) ran an integrated arts program for children and teenagers.

"My last few productions directing adults were not very exciting," he says

dryly. "So I stayed with children for many years."

Then in 1984 came an acting project he couldn't resist:

Taper, Too's landmark production of "In the Belly of the Beast," the

hellish memoirs of incarcerated murderer/writer Jack Abbott.

"It was a hair-raising experience," he says bluntly.

"Doing that play really took its toll. 'Homecoming' has a thread of evil,

but 'Belly' is about evil." In spite of its physical and psychic

rigors, the show was a godsend for Robinson:. He later played it at the

Taper, toured to Australia and New York and won an L.A. Drama Critics

Circle Award for his performance. Most importantly, it took Robinson's

career—and the way he was perceived by the industry—to a new level. "It

brought me back to L.A., and back to the business on my own terms," he

says simply. "I have no apologies. This is the work I want to do, what I

want to take to my grave."