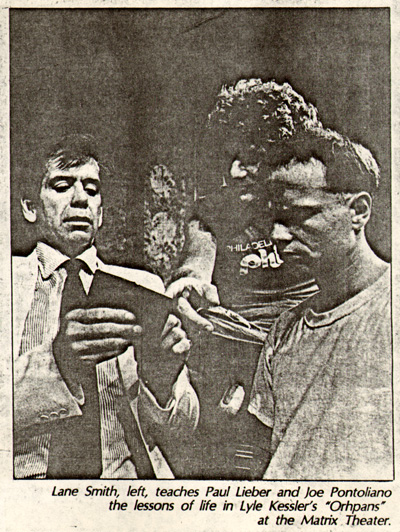

DRAMA-LOGUE, Sept. 1-7, 1983

by Polly Warfield

Who was that masked man? We may well

wonder as the mysterious, dedicated benefactor of "Dead End Kids"

and orphans swings out the door with only his briefcase in his hand

to disappear forever down a nondescript North Philadelphia street.

For Harold is the Lone Ranger, Zorro, Superman, even maybe (dare we

say it?) a surrogate of Jesus Christ. The lives he touches and

redeems are forever altered. It is Harold, played to stunning

perfection by Lane Smith, who lifts Lyle Kessler's play into

joyousness and makes it the gem it is.

The play is not to be taken totally realistically

despite its modern idiom; it is part fantasy, fable, old-fashioned

fairytale. Its sentiment is Gene Stratton Porter and Horatio Alger Jr.

updated. It is cracking good entertainment, comedy and suspense. It is

also metaphysical and allegorical. It's easy enough to point out flaws of

contrivance and credibility, such as where did sequestered Phillip (shades

of Cinderella) get that stiletto-heeled red satin slipper he so cherishes?

Since he and delinquent elder brother Treat are orphans of the storm, who

took care of this presumably helpless kid when Treat was in detention

hall? What use could a youth apparently so retarded make of a contraband,

concealed Webster's Collegiate and what interest would he have in

multi-syllable words? And why can't he figure out how to get into those

splendid yellow loafers Harold buys him when (even though he can't tie the

laces) he can get into his old sneakers? I will not cavil at such

contrivances for they are theatrically effective ways of making legitimate

points. And the points they make are well worth making.

Orphans is given the kind of lustrous, polished

production we have come to expect of Joseph Stern, who is gaining the

reputation of a flair for infallibility. The cast is well-chosen,

wonderful and admirably differentiated, and John Lehne's expert direction

establishes its intrinsic rhythm while establishing Lehne in the forefront

among Los Angeles directors. Paul Lieber's sharp, tough, street-smart

Treat is volatile and dangerous as a hand grenade. His kind of

retardation, Harold shows us, is more grievous than Phillip's, and both

are a matter of environment and deprivation. Joe Pantollano's gentle,

timid Phillip is irresistible with the sweet, eager to please innocence of

childhood. Down to his twisted smile and raspy voice with its occasional

spurts of explosive volume, Lane Smith is marvelously right for ex-orphan,

self-made millionaire, rough-cut hero Harold, pure in heart though

associate of gangsters and thugs. The strength and steel of his intellect

and maleness are enriched into wondrous treasure by his extraordinary

(superhuman?) tenderness and love. With his power and need to nurture,

forgive, redeem "dead end kids" he embodies the essence of fatherhood,

just when we might have been in danger of doubting its existence, and

makes it the emotional equal of motherhood, which has received a much

better press. Harold is gratifyingly infallible, invincible, indomitable,

apparently indestructible and good, as opposed to what we've seen

too much of lately: impotence, helplessness and evil. Just what we need

when we need him.

D. Martyn Bookwalter's set is so true it's imprinted on

our memories. We've seen it all before; it's so familiar with its dingy

details, spots on the wall where pictures no longer hang, scruffy

wallpaper, dispirited window shades. In the second act, two weeks later,

we see small miracles of change with Harold's influence. Martin Aronstein

puts his prestigious talent at the service of Equity-waiver and lights the

old family home with pale sepia memory tints of old photos; it lingers

lovingly on a chosen subject as each scene ends. Doug Spesert's costumes

indicate the orphans' improved condition, while Harold's long journey from

orphanhood is shown in his consistent GQstyle, always impeccable. Jon

Gottlieb's sound is, as ever, fitting and also unobtrusive. J.A.C.

Redford composed the appropriate and lovely incidental music.

Orphans can be taken to the heart as a rare treat,

funny, poignant, exciting and best of all inspiriting.

L.A. WEEKLY, Sept. 2-8, 1983 (PICK OF THE

WEEK)

by Joie Davidow

Treat is a petty thief. He keeps himself and his

brother Phillip in mayonnaise and Starkist tuna by stealing wallets,

watches and rings. Phillip is afraid to go outside. He thinks tie's

allergic to a lot of things, especially fresh air. Phillip can't even tie

his own shoelaces, and Treat likes it that way. It gives him a certain

authority over his brother. The boys are orphans, you see. Dad ran away

from home long ago, and Mom died when they were still little kids, so

they've been fending for themselves in the family's old North Philadelphia

house ever since. One day, Treat brings home Harold, a drunken

middle-aged man wearing an expensive suit. Harold has a leather briefcase

full of negotiable securities and a wallet full of credit cards. Treat

thinks he's hit paydirt this time. Harold is full of stories about his own

childhood spent in an orphanage, and he's certainly glad he found Treat in

that downtown bar, that he finally met a "real dead end kid." Treat

decides to kidnap Harold and hold him for ransom, but Harold turns the

tables on Treat and pulls a gun on him. "I'm not going to hurt you,"

Harold says, "I'm just going to hire you." And so begins Harold's

rehabilitation of brothers Phillip and Treat. But who is Harold? Is he a

gangster running from the mob, a self-made millionaire, a guardian angel

come to rescue these derelict boys? John Lehne has beautifully directed

this world premiere of Lyle Kessler's play, finding its naive charm,

taking advantage of every laugh in the dark comedy, and adding a few

slapstick chuckles of his own. The performances are all quite wonderful

Paul Lieber's swaggering, violent Treat, Joe Pantoliano's innocent,

slobbering Phillip and Lane Smith's suave and kindly Harold. Their

characterizations are neatly balanced, part real people part allegorical

creatures, and both Lieber and Pantoliano manage liquid smooth transitions

as Harold dresses them up and civilizes them. D. Martyn Bookwalter's

set is a nice combination of sleazy authenticity and humor.

DAILY BREEZE NEWS-PILOT, Sept. 30, 1983

"ORPHANS" SPINS A TALE OF HOPE AND DISCOVERY

by Sandra Kreiswirth

Lyle Kessler's "Orphans" at the Matrix Theater in Los

Angeles is a fascinating, slightly flawed fable/fantasy about love, trust

and discovery.

Joseph Stern has delivered yet another excellent

production under the auspices of Actors For Themselves enhanced by John

Lehne's fine direction and strong performances by Joe Pantoliano, Lane

Smith and Paul Lieber.

This world premiere captures' the imagination at once.

It's funny, sad, depressing, uplifting and sometimes farfetched.

Set in a run-down house in North Philadelphia,

"Orphans" is the tale of two brothers one a mugger, the other an

apparently retarded recluse whose lives are changed when their kidnap

victim takes charge of their lives.

Treat (Lieber) is the older brother. A grown-up

juvenile delinquent who supports himself and his brother by relieving

people on the street of their valuables. He's not adverse to cutting up

his victims a bit to keep them quiet, then can't understand why they verbally

abuse him. Except for a stint in reform school, he's taken care of his

brother ever since their mother died when they were children. He's

provided a home of sorts for his brother but emotionally only delivered

custodial care along with lots of Bellman's mayonnaise and Star-Kist tuna.

Phillip (Pantoliano) is an innocent. He dresses in torn

clothes and shoes with untied laces because he's never been taught how to

make a knot Treat forces him to stay in the house because years ago he had

an allergic reaction outside. He watches old movies and game shows, knows

the brand name of every prize on "The Price is Right" and spends a lot of

time hiding in the upstairs closets filled with his mother's old coats.

Treat tells Phillip he has no intellect, yet Treat

occasionally finds Words underlined in the newspaper. When pressed,

Phillip makes up fantasies about Errol Flynn hiding in the house. Errol

must have underlined the words. Ultimately Treat not only discovers a

dictionary hidden inside the sofa, but other books, too.

What exactly is Phillip doing when Treat's not home?

And if he knows enough to be able to read, why is he still there? He

treasures a red satin pump he's gotten from Somewhere but where? Those

questions go unanswered.

Harold (Smith) is Treat's victim - an expensively

dressed man he meets downtown and lures home to rob. Harold, urbane and

all-knowing, comes with Treat because he sees him as a little Dead End

Kid. Harold passes out drunk waking to find himself bound and gagged. A

fan of Houdini, he easily frees himself the next morning while Treat's on

the streets leaving a helpless Phillip to watch with wide-eyes. Does

Harold escape?

Of course not He stays to teach these brothers the

lessons of life. He tells them stories about being an orphan newsboy in

Chicago and wearing copies of the Chicago Tribune to ward off the

icy winds. He offers Phillip affection - "I bet your shoulders are dying

for an encouraging squeeze which is just what he needs. No more worry

about tying shoe laces, Harold promises Phillip slip-on loafers. Any

color. And he's not even mad at Treat. Instead he offers him a job as his

bodyguard his background is shady.

By act two, Harold has moved in, decorated the

apartment and put Treat on his payroll. He's dressed Phillip in white wool

pants and pink silk shirt. Pale yellow loafers grace his feet Treat has

traded his fatigues and torn T-shirts for Pierre Cardin suits, and he's

become intimately acquainted with Harold's American Express card.

As he sings "If I Had the Wings of an Angel," Harold

has all the answers. He appears in the brothers' lives suddenly as if sent

by some mysterious force. He's Robin Hood. He's the guardian angel He

explains everything so clearly.

He's an evangelist, a psychologist, a friend. What ever

the problem, he has special insight. For Phillip, he has the ultimate key

to unlocking the door of life ifor the child/man the answer to where he

is in time and space. What is it? A street map of Philadelphia. That's

apparently all it takes. Treat's problems are deeper not to be cured so

easily.

Ultimately Kessler's ending is a bit of a fairy tale

wrap-up. But getting there

is both fun and touching. Despite the fact that Kessler

asks us to accept a few shaky propositions, especially about Phillip,

"Orphans" is imaginitive in its concept and keeps the audiences' attention

from start to finish. Kessler's characters are well drawn with each one's

language unique to himself.

Pantoliano's Phillip is endearing. He's wonderful to

watch in his confused innocence and even more interesting as he discovers

life's simple answers. Lane gives Harold a mysterious other-world quality.

He could very easily be an imaginary character. And Lieber, the most

traditional member of this trio, is a good contrast to the other two an

example of a hustler existing purely on instincts most 'of them bad.

Lehne's direction has resulted in tight ensemble work

with excellent pacing. The first act is over before you know it In fact

the evening (two acts three scenes in each) zips by. D. Martyn

Bookwalter's seamy living room set changes from musty, old, cluttered and

dirty to well-appointed and chic between acts. When the lights go out, the

wallpaper becomes star-studded.

Doug Spesert's costumes, Martin Aronstein's lighting

and Jon Gottlieb's sound design live up to the excellent standards we've

come to expect from an Actors For Themselves Production.

STAR-NEWS, Friday, Sept. 2, 1983

"ORPHANS" MAKES SENSE

by JANET NORSE

Hey, what is it with this guy, anyway? Kidnapped by a

thug, guarded by a seemingly demented recluse, he shows no fear. He frees

himself with surprising ease, yet doesn't escape. He helps these two

rejects of society. He likes these two rejects of society. Who does

this guy think he is?

Audience members can answer that question for

themselves at Lyle Kessler's "Orphans," a moving and delightful parable

now at the Matrix Theatre in Hollywood. Actors for Themselves, the company

that presented last year's multi-award-winning "Betrayal," has done itself

proud in a very different kind of play.

John Lehne has directed "Orphans" with a fine feeling

for both the comedy and the deeper meanings of the script. The result is

coherent and thoughtful, and the shifting relationships between the

characters make sense throughout the play.

Paul Lieber, playing the mugger, Treat, gives a

multi-level performance. His coldness and greed are incontestable; but so

is his love for his reclusive brother, although he's unable for most of

the play to express that love as more than a threatened possessiveness.

Joe Pantoliano gives a remarkable performance as

Phillip, Treat's brother. This is a role that could have been easy to

overdo, to caricature, but Pantoliano never stoops to that. In his

smallest facial expressions and gestures, he creates a real person with a

real desire for a better life.

The whole play hinges on Harold, the mysterious

stranger who takes this unlikely pair under his wing, and Lane Smith

responds fully to the challenge. He is knowing without being judgmental,

pragmatic without being unloving, humorous without flippancy.

D. Martyn Bookwalter's set sums up the play

beautifully: a once-beautiful house gone hopelessly to seed in the first

act, made comfortable and home-like in the second. Martin Aronstein's

lighting design is equally appropriate.

Doug Spesert's costumes are right for each character,

most particularly for Phillip's second-act evolution: socially acceptable,

but still slightly off-the-wall. The original music for the show, composed

by J.A.C. Redford, is warm and cheerful.