REVIEWS:

BackStage West

Reviewed by Rob Kendt

There is rare pleasure to be had

in the Matrix's now-regular double-casting, in which two actors are

assigned each role in each production and then mixed and matched

throughout the show's run in various combinations. With a play as

resonant and troubled as Larry Atlas' Yield of the Long Bond,

this pleasure is especially acute, if problematic. Atlas' bleak love

triangle between a rogue Wall Street investor, a slick young lawyer,

and a down-at-heels Episcopal pastor is so perorative and schematic,

giving each of its three characters more fourth-wall-breaking

speeches than real interaction—more to say to us than to each

other—that it represents a sort of acting triathlon, a three-way

show of dexterity and force. And since Atlas' characters are so

atomized and, in director Andrew J. Robinson's artful, worried

staging, so sharply drawn, it is easy to imagine all six actors

interchanging willy-nilly without much variation in the production's

impact.

That impact is no less harsh for

its seeming, at bottom, profoundly confused. In pitting a sleek,

beautiful young professional woman between a rich vulgarian and a

queasy idealist and making her the battleground (unfortunately quite

literally) for an intensely serious debate on faith, hope, and love,

Atlas risks the canard that he's doing what men, and male writers,

have always done: Looked to women for redemption, even as we deemed

them in need of our rescue.

The young attorney Ellen Kastner

(Julia Campbell, Anna Gunn) is a fallen angel at best, a

squeaky-clean Princeton girl unloosed into the high-powered evil and

low-level spiritual drudgery of big business, where she learns to

play its deadly garae as perfectly as she used to say her prayers.

That game includes getting into bed with such unsavory charmers as

Paul Rosario (Gregory Itzin, Ian McShane), a man with the kind of

terrifying self-assurance that dares a challenge. He meets his match

in Ellen, who at first plays along with his sexual feints and

degradations but soon loses the stomach for them,

suggesting—ostensibly as a practical matter—that he get involved in

charity work to offset the damage of an impending SEC prosecution.

That leads them into the weak

thrall of John Shelly (David Dukes, Byron Jennings), a priest with a

modest think-tank project to promote spiritual values in a soulless

age—which of course leads to Ellen's wavering consideration of these

issues, and in general to the level of windy, contrarian

philosophizing on which Atlas clearly wants to operate. He

introduces an increasingly lurid and incredible plot, and several

new moral wrinkles, into the mix, but even the sudden reversals and

telling observational details are as schematic as a prospectus, his

dialogue often embarrassingly blunt and self-revealing.

How to play this uneasy mix of

monologue, flashback, and confession? Under Robinson's unwavering

gaze, these six actors manage, with varying degrees of passion,

intelligence, and courage, to elevate the work into the rumination

it wants to be. McShane captures Paul's arrogance and steel, Itzin

his rue and sick sense of play; Gunn shows us Ellen's terrible

complicity in her own loss of innocence, while Campbell suggests the

possibly more terrible human fiber that has survived it. Jennings

and Dukes have the most difficult, and most schematic, transition of

the play; while the tender Jennings makes his priest's turnabout

both brutal and pitiful, the edgier Dukes makes it movingly

pathetic, a true human loss.

Deborah Raymond & Dorian

Vernacchio's sparse set, Keith Endo's busy lights, and Peter

Erskine's portentous music are all as deliberate, and as ultimately

haunting, as is the acting, consolidating the Matrix's well-deserved

reputation as one of the boldest and brightest showcases for stage

talent on this coast.

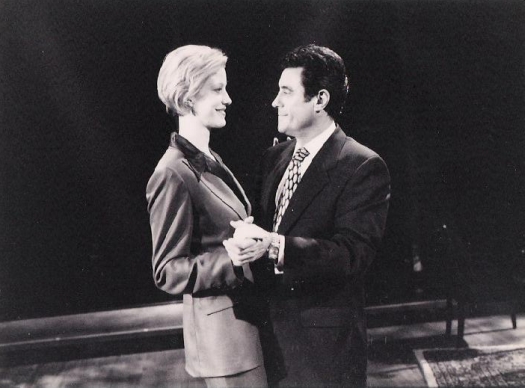

L-R: Anna Gunn & Ian McShane

The Hollywood Reporter

Reviewed by Ed Kaufman

Larry Atlas' "Yield of the Long Bond" has a little of

everything: a bit of humor; a lot of intense philosophizing about the

mysteries of love, the earthly and the spiritual; and a morality tale

about faith vs. greed. And in the second act, the play shifts to a

psychological whodunit and murder mystery that is full of soul-searching,

irony and angst.

Despite using some patches of rhetoric in place of

dramatic writing, Atlas is a first-rate playwright, able to move his

actors with ease and assurance. Credit Andrew J. Robinson's savvy,

free-flowing, expressionistic direction, which keeps things constantly

moving.

"Yield" — having its world-premiere run at the Matrix —

tells the story of Paul Rosario (the thoroughly convincing Gregory Itzin),

a ruthless, arrogant, base, hedonistic, foul-mouthed Manhattan investor

whose net worth is roughly $400 million. When he learns from his

lawyer/lover Ellen Kastner (Julia Campbell) that he is being investigated

by the SEC for insider trading and stock manipulation, she convinces him

change his image and make a large donation to the Parish Project run by

Father Shelley (Byron Jennings). All this for Rosario's respectability

when it comes time for his trial.

Shelley's project wants to "promote thought in a

thoughtless environment"; it includes a newsletter and the commissioning

of a book promoting a spiritual life. Soon Ellen is caught between the the

sacred and the profane worlds.

Writer Atlas has the three square off with one another:

the corrupt and cynical loner Rosario, the once-idealistic Ellen (who seem

fit only for each other) and Shelley, the Episcopalian priest with an

agenda. Seemingly, it's the classic struggle of Good vs. Evil. Only Atlas

has some updated opinions and observations of his own.

Act 1 ends with Ellen's murder, and Act 2 becomes the

whodunit It also includes the unraveling of who the trio is, with all

sorts of twists and turns, the surfacing of old memories and revelations

that are quite effective and really touching.

As always, the Matrix Theatre production features two

casts.

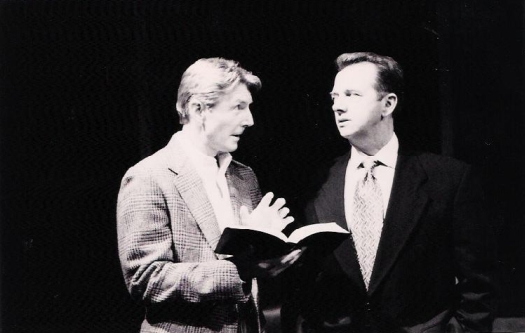

L-R: Byron Jennings & Gregory Itzin

Rave! Magazine

DRAMAS UNVEIL EMOTIONAL WALLOP

By DEBBI K. SWANSON

For the first time since the Matrix Theater in Los

Angeles began single production revivals five years ago, the theater

presents two new contemporary American plays in repertory: "The Water

Children" and "Yield of the Long Bond." Both are double cast.

In Larry Atlas' rather heartless work, "Yield of the

Long Bond," the second of the Matrix plays in repertory, a man of greed

faces off against a man of God. You could say it's a contest of epic

proportions — and the woman in the middle gets soaked.

Using the same set as "The Water Children," Ian McShane is Satan — the soulless Paul Ro-sario, a charismatic, impeccably dressed, morally bankrupt tycoon on the Verge of being financially

bankrupt as well.

Byron Jennings is the voice of God as John, a humble

pastor in corduroy with his own repressed issues. Anna Gunn is the trapped

Ellen, a high-powered attorney in excessively expensive and sexy suits who

has no life except to be at Rosario's beck and call.

She's lost because she's denied her own feelings for so

long in the attempt to bill those all-important hours. She's become a

victim in a nasty game.

The language of this play is fast and furious, Rosario

spewing out financial terms like they were his first language. And as a

boy wonder with stocks, they nearly were.

Under Andrew J. Robinson's direction, the first act is

witty, sharp, funny and cold. At the opening of Act Two, we find the men

in jail, unsure which of them is the inmate. The story becomes Ellen's,

focusing on her emptiness and longings. It becomes a dark, mean, series

confrontations. In flashback. Ellen opens up to John, to confess her sins

and emptiness.. That is her mistake.

Keith Endo's lighting and Audrey Eisner's costuming are

first rate.

The performances are also excellent...